By Narissa Lewis

A key focus of our project is to broaden our understanding of employability development and how we make development opportunities more accessible to students. While embedded approaches are ideal, students may develop employability skills through co-curricular activities however these are often inaccessible to non-traditional students including those from ethnic minorities (Owens et al., 2010) lower socio-economic groups (Budd, 2016; Byrom & Lightfoot, 2013; Reay, Crozier & Clayton, 2010; Redmond, 2006) first-generation (Hirudayaraj, 2011; Owens et al., 2010) and indigenous students (Pechenkina, Kowal & Paradies, 2011). In a workshop run by Susan Geertshuis and I at the Tertiary Education Research in NZ (TERNZ) conference on the 29 November 2017, 24 academic development and lecturing staff from several tertiary institutions explored the important topic of how we can better serve non-traditional students.

Susan began the workshop inviting participants to share their experiences of university and how it shaped their professional careers with a catch – participants had to demonstrate this with playdough. Participants then shared the narrative behind their creations and while university developed and shaped participants into who they were today, many recalled the experience as isolating and difficult, particularly if you were a student who was unfamiliar with university life either through being first in family or as an international student. As one participant’s suitcase model depicted, it was such a difficult experience that she packed her suitcase and traveled instead!

The exercise highlighted the irrelevance of the term non-traditional given many participants might be considered non-traditional themselves. We realised that if anything, the traditional student who has followed a linear, uninterrupted pathway into university, with family members who attended university before them, might be considered the exception. As someone who might be considered a non-traditional student myself, I believe the term is outdated and needs a rethink. Nevertheless, literature reports particular students as ‘non-traditional’ and they often experience different career outcomes to other students even if they graduate with equal or better degrees due to unfamiliarity with higher education, limited resources and conflicting priorities (Lehmann 2012; Reay, Crozier & Clayton, 2010; Redmond, 2006).

Reflecting on their own institutions and experiences, participants constructed a challenge or barrier that non-traditional students face. Some of the constructions were described as insurmountable walls and ladders that appeared difficult to climb, racial stereotypes and institutions that favour dominant groups, tensions of walking in two worlds and ongoing tensions of cultural values.

A participant describes the two worlds and racial stereotypes that she encountered as a Māori student.

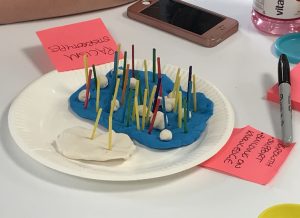

Participants were then invited to turn their ‘barrier’ into an ‘enabler’. Models morphed into creations that depicted support systems: stepping stones and props were added to support the climbing of walls, like-minded role models were added to pull others up ladders, squares that depicted students not fitting in morphed into wheels to facilitate a smoother transition through multiple worlds in which these students find themselves in.

Once the enablers were constructed, participants brought their enablers together to construct a model campus that supports the needs of all students. Common themes amongst the three groups was the need to have a system that embraces and respects diversity. In institutions that favour dominant groups, participants believed that if non-traditional students are to truly thrive in our institutions, key decision makers and systems need to reflect the diverse cultures that students come from. Model campuses also included connections with role models and services that facilitate the development of employability capabilities. All groups also emphasised the need for end-to-end services from enrolment to graduation. Several participants also raised the importance of pre-tertiary career guidance and how career decisions start well before students enrol in our institutions. The campuses brought home the fact that such systems require significant resourcing and cultural changes. Nevertheless, the exercise unearthed the need for holistic approaches to develop employability capabilities of our students.

Model campus 3 – a system that recognises and celebrates the diverse outcomes of students – bird, duck or other!

The session ended with key takeaways that participants would implement into their own practices. Although the ideal model campuses would require significant changes, the exercises prompted participants to consider their own practices. Diversity was considered significant and several participants commented on how they could make their content and the way in which they deliver their courses more diverse. Several also mentioned the need to understand services that students could tap into to develop their employability capabilities within their own institutions. While the session didn’t culminate in a silver bullet to support the needs of non-traditional students, it did generate rich discussion about the relevance of the term and how we might better serve the needs of all students based on our own experiences.

References

Budd, R. (2016). Disadvantaged by degrees? How widening participation students are not only hindered in accessing HE, but also during – and after – university. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2016.1169230

Byrom, T., & Lightfoot, N. (2013). Interrupted trajectories: the impact of academic failure on the social mobility of working-class students. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(5-06), 812–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816042

Hirudayaraj, M. (2012). First-Generation Students in Higher Education: Issues of Employability in a Knowledge Based Economy. Online Journal for Workforce Education and Development, 5(3). Retrieved from http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ojwed/vol5/iss3/2

Owens, D., Lacey, K., Rawls, G., & Holbert- Quince, J. (2010). First-Generation African American Male College Students: Implications for Career Counselors. Career Development Quarterly, 58(4), 291–300.

Pechenkina, E., Kowal, E., & Paradies, Y. (2011). Indigenous Australian Students’ Participation Rates in Higher Education: Exploring the Role of Universities. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 40, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajie.40.59

Reay, D., Crozier, G., & Clayton, J. (2010). “Fitting in” or “standing out”: working-class students in UK higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902878925

Redmond, P. (2006). Outcasts on the Inside: Graduates, Employability and Widening Participation. Tertiary Education and Management, 12(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-006-0002-4

Recent Comments